A defining quality of good fiction, and especially good science fiction, is that it makes the familiar strange and the strange familiar. Detective fiction goes a bit further by seeking to make significant that which is (seemingly) ordinary and to make clear that which is (temporarily) opaque. Asimov, in this sequel to another futuristic detective novel (Caves of Steel), expertly combines those feats of literary alchemy into a lively, thought-provoking entertainment.

Many centuries hence, a murder occurs on the Outer Worlds planet of Solaria, where crime is practically nonexistent—and so is any kind of police force. Peculiar facts about the killing raise the need for a serious inquiry. Whoever killed Rikaine Delmarre bludgeoned him at close range, but no weapon turned up in the initial search of the crime scene. Evidence supplied by robots establishes that the only other human near that scene was the victim’s wife, Gladia, yet she fell unconscious around the time of the murder and had no chance to dispose of a weapon. Faced with this quandary, the Solarian powers-that-be deign to invite a mere Earthman to work the case on their behalf. Elijah Baley, a “plainclothesman” from New York City, thus finds himself traveling millions of miles to a planet known for its “naked sun.” (In the Earth of this imagined future, people live in subterranean “caves of steel” and have no direct experience of the star that lights their galaxy.) There, Baley reunites with Daneel Olivaw, a “positronic” robot who served as his sidekick in the previous adventure. Soon after Baley and Olivaw begin their probe, someone attempts a second murder. As the two detectives communicate via holographic projection with Hannis Gruer, the planet’s head of security, they watch him suddenly lurch into convulsions after sipping from a glass of water. Clearly, the glass contains poison. But who could have administered it, and how? Like other Solarians, Gruer lives alone on a vast estate; only his robots are able to come anywhere near him, and robots are hard-wired to avoid causing harm to their human masters.

Many centuries hence, a murder occurs on the Outer Worlds planet of Solaria, where crime is practically nonexistent—and so is any kind of police force. Peculiar facts about the killing raise the need for a serious inquiry. Whoever killed Rikaine Delmarre bludgeoned him at close range, but no weapon turned up in the initial search of the crime scene. Evidence supplied by robots establishes that the only other human near that scene was the victim’s wife, Gladia, yet she fell unconscious around the time of the murder and had no chance to dispose of a weapon. Faced with this quandary, the Solarian powers-that-be deign to invite a mere Earthman to work the case on their behalf. Elijah Baley, a “plainclothesman” from New York City, thus finds himself traveling millions of miles to a planet known for its “naked sun.” (In the Earth of this imagined future, people live in subterranean “caves of steel” and have no direct experience of the star that lights their galaxy.) There, Baley reunites with Daneel Olivaw, a “positronic” robot who served as his sidekick in the previous adventure. Soon after Baley and Olivaw begin their probe, someone attempts a second murder. As the two detectives communicate via holographic projection with Hannis Gruer, the planet’s head of security, they watch him suddenly lurch into convulsions after sipping from a glass of water. Clearly, the glass contains poison. But who could have administered it, and how? Like other Solarians, Gruer lives alone on a vast estate; only his robots are able to come anywhere near him, and robots are hard-wired to avoid causing harm to their human masters.

To read this book during the 2020–2021 pandemic is to experience a shock of recognition—a glimpse of the present as foreshadowed by a decades-old vision of the future. The people of Solaria, like those of plague-scarred Earth in the time of Covid-19, interact with other humans almost entirely by remote means. Asimov posits a technology that enables what Solarians call “viewing,” and his descriptions of that practice suggest a three-dimensional version of the screen-mediated forms of engagement (Zoom meetings and the like) on which people today increasingly depend. Solarians, who descend from human Earthlings, differ from present-day humans in that they prefer viewing to its in-person alternative, which they call “seeing.” In effect, Solarians have replaced the need for human contact with a reliance on legions of supremely advanced robots. That feature rings a contemporary bell, too. Denizens of Earth do not have high-functioning anthropomorphic machines to assist them during long months of pandemic isolation. But, like their counterparts on Solaria, they struggle to understand and manage the devices (smart and not-so-smart) that they have made.

The peculiar conditions of Solaria are a critical factor in the crimes of apparent impossibility that Baley must solve. These puzzles, in fact, are keenly satisfying because they arise from—and hinge on—those very conditions. Each actual or attempted murder appears to lie outside the realm of the possible because (and only because) it takes place amid a cluster of social customs and logistical circumstances that are unique to the world that Asimov has constructed. For example, the visceral aversion that Solarians (most of them, anyway) have to sharing physical space with other humans creates a situation in which the killing of Delmarre and the attack on Gruer seem to defy explanation. Likewise, the Three Laws of Robotics, which are part of a system that Asimov has built into this world, set precise limits on the kinds of violence that robots can either perpetrate or allow to happen in their vicinity. To crack the mysteries at hand, Baley must tease apart the implications of these and other features of Solarian civilization.

Asimov manages the mystery plot with high professionalism, and he deals competently with adult themes that involve matters of human intimacy and human destiny. Even so, Naked Sun displays traces of a juvenile sensibility that was fairly common in mid-20th-century science-fiction writing.  Too often, a gee-whiz tone overtakes Asimov’s otherwise serviceable prose, and his lead character, Baley, comes across as an earnest, boringly upright fellow—less as an heir to Philip Marlowe than as a law-enforcement version of Buck Rogers. In addition, there is a subplot that concerns the threat of intergalactic war, and although Asimov handles that story line with some complexity, its presence here brings a pulpy space-opera element into what should be (and mostly is) a tightly focused tale of investigation and discovery.

Too often, a gee-whiz tone overtakes Asimov’s otherwise serviceable prose, and his lead character, Baley, comes across as an earnest, boringly upright fellow—less as an heir to Philip Marlowe than as a law-enforcement version of Buck Rogers. In addition, there is a subplot that concerns the threat of intergalactic war, and although Asimov handles that story line with some complexity, its presence here brings a pulpy space-opera element into what should be (and mostly is) a tightly focused tale of investigation and discovery.

Like the best science fiction of its era, the novel also explores big ideas in a big, none-too subtle way. As the tale unfolds, Asimov presents a series of conversations between the Earthman sleuth and several of the Solarian suspects, including a sociologist, a roboticist, and the erstwhile assistant of the first victim, who had been the planet’s foremost “fetal engineer.” These conversations teem with anxious speculations about parenthood and family life, about population growth and the fate of nations (or, indeed, of entire planets), about humanoid machines and the humans who create them—preoccupations that were bubbling just under the surface of American culture during the 1950s. To reach Solaria, Baley spans many lightyears in a space capsule. Asimov, meanwhile, brings something else back from his fictive journey: a time capsule.

[ADDENDUM: A recent column in The New York Times by Paul Krugman spurred me to read this book at this time. Krugman flags the somewhat uncanny way that Asimov prefigured life under semi-lockdown. Naked Sun features “a society in which people live on isolated estates, their needs provided by robots and they interact only by video,” the columnist writes. “The plot hinges on the way this lack of face-to-face contact stunts and warps their personalities.”

So my review here steals just a bit from Krugman. It also steals a bit from myself. Looking back at my piece on the prequel book, Caves of Steel, I see that that I’ve touched on some of the same themes again—the science-fiction-as-time-capsule idea, the motif of using futuristic conditions (such as “laws” that govern robot behavior) to drive an impossible-crime plot. So I’m less original in this instance than I could be. Then again, the same is true of Asimov.]

Among the central players in the drama are Francis Xavier Benedik, a partner in a London investment firm; his son, Anthony Xavier Benedik, who is also a partner; a third partner, Samuel Rickworth; and Rickworth’s daughter, Petronella (“Peter”), who is Anthony’s fiancée. Supplementing the cast are assorted clerks, secretaries, and servants who work either at Rynox House, where the investment firm keeps its offices, or at the Benedik home in Mayfair. (

Among the central players in the drama are Francis Xavier Benedik, a partner in a London investment firm; his son, Anthony Xavier Benedik, who is also a partner; a third partner, Samuel Rickworth; and Rickworth’s daughter, Petronella (“Peter”), who is Anthony’s fiancée. Supplementing the cast are assorted clerks, secretaries, and servants who work either at Rynox House, where the investment firm keeps its offices, or at the Benedik home in Mayfair. ( As is typical of

As is typical of  In its setting and its setup, the

In its setting and its setup, the  Solving this conundrum requires both painstaking analysis and bold intuition. (“We have to take hold of our reason by the right end,” Rouletabille notes.) But Leroux, having contrived this feat of deception, proceeds to swaddle it in layers of over-embroidered, shoddily sewn story material. As a result, when the time comes to explain this sleight of hand, what should be an adroit revelation becomes a labored and almost impossible-to-follow disquisition.

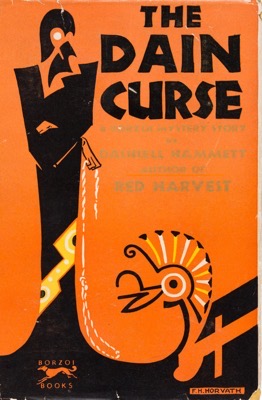

Solving this conundrum requires both painstaking analysis and bold intuition. (“We have to take hold of our reason by the right end,” Rouletabille notes.) But Leroux, having contrived this feat of deception, proceeds to swaddle it in layers of over-embroidered, shoddily sewn story material. As a result, when the time comes to explain this sleight of hand, what should be an adroit revelation becomes a labored and almost impossible-to-follow disquisition.  Many corpses accumulate along the way, and the only factor that appears to link these deaths is Gabrielle. A possible explanation for all of this violence—though not one that the Op accepts—is a curse that supposedly afflicts the Dain family, from which Gabrielle and her mother descend.

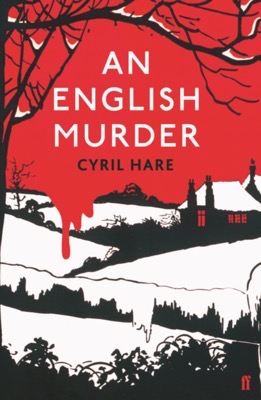

Many corpses accumulate along the way, and the only factor that appears to link these deaths is Gabrielle. A possible explanation for all of this violence—though not one that the Op accepts—is a curse that supposedly afflicts the Dain family, from which Gabrielle and her mother descend. In a sequence of early scenes, various tensions—personal, familial, and political—simmer in the interaction among these characters. As midnight approaches on Christmas Eve, they gather in the drawing room at Warbeck Hall for a traditional holiday toast. Even then, a trace of suspense lingers over the question of who will receive a dose of cyanide in his or her celebratory glass.

In a sequence of early scenes, various tensions—personal, familial, and political—simmer in the interaction among these characters. As midnight approaches on Christmas Eve, they gather in the drawing room at Warbeck Hall for a traditional holiday toast. Even then, a trace of suspense lingers over the question of who will receive a dose of cyanide in his or her celebratory glass. The Montefierrow twins, the villains who drive this very

The Montefierrow twins, the villains who drive this very  In various combinations, these characters race across city streets—and back and forth to a small upstate town—in vivid, cinematically paced scenes. An actual movie adaptation, in fact, might have improved the

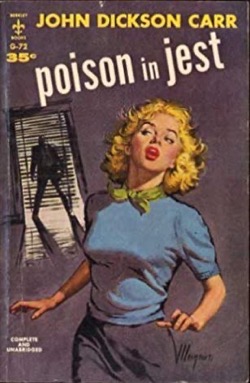

In various combinations, these characters race across city streets—and back and forth to a small upstate town—in vivid, cinematically paced scenes. An actual movie adaptation, in fact, might have improved the  Apart from a prologue and an epilogue, all of the action in Poison in Jest occurs at the Quayle house or on its grounds. Marle is visiting the Quayles after a decade of traveling in Europe, and he soon finds that he has ventured into a classic viper’s nest, a household in which several members could become—and do become—the object of a killer’s wrath. Denizens of the house include Judge Quayle, his bedridden wife, and four of their five adult children. The fifth offspring, a hot-tempered fellow named Tom, had fled the house a few years previously. Also resident in the home is Walter Twills, the husband of Clarissa (née Quayle) and a man of independent means. Those means, in fact, are keeping the Quayle ménage financially afloat, and a covetous attitude toward the Twills fortune appears to drive a series of poisonings that take place on the night of Marle’s visit. Not all of these homicidal efforts hit their target, but one of them does, and more violence happens in its wake. Moment by moment, the

Apart from a prologue and an epilogue, all of the action in Poison in Jest occurs at the Quayle house or on its grounds. Marle is visiting the Quayles after a decade of traveling in Europe, and he soon finds that he has ventured into a classic viper’s nest, a household in which several members could become—and do become—the object of a killer’s wrath. Denizens of the house include Judge Quayle, his bedridden wife, and four of their five adult children. The fifth offspring, a hot-tempered fellow named Tom, had fled the house a few years previously. Also resident in the home is Walter Twills, the husband of Clarissa (née Quayle) and a man of independent means. Those means, in fact, are keeping the Quayle ménage financially afloat, and a covetous attitude toward the Twills fortune appears to drive a series of poisonings that take place on the night of Marle’s visit. Not all of these homicidal efforts hit their target, but one of them does, and more violence happens in its wake. Moment by moment, the  Grey, a thoroughly modern woman with an air of mystery about her, beguiles both McKell men and puts herself in competition with the McKell matriarch. So, when this “other woman” succumbs to a gunshot in her penthouse apartment, the obvious suspects in her murder are a quick elevator ride away. The story relies on strong passions—or at least the idea of strong passions—to yield potential motives for the killing. Yet its main characters (and its minor ones, too) exist only in two dimensions; they are, in essence, simple shapes that happen to intersect on a plane.

Grey, a thoroughly modern woman with an air of mystery about her, beguiles both McKell men and puts herself in competition with the McKell matriarch. So, when this “other woman” succumbs to a gunshot in her penthouse apartment, the obvious suspects in her murder are a quick elevator ride away. The story relies on strong passions—or at least the idea of strong passions—to yield potential motives for the killing. Yet its main characters (and its minor ones, too) exist only in two dimensions; they are, in essence, simple shapes that happen to intersect on a plane. The

The