In the world of visual art, the detective novelist finds a milieu rife with potential intrigue and rich in deceptive possibility. Artists, to keep from starving, must beguile or placate obtuse patrons, arrogant critics, and other figures whose whims will shape their cultural reputation—and their market value. They operate in a realm of pure subjectivity; their worth and that of their work lie in the eye of one fickle beholder after another. Among all but the most elite practitioners, competitive jousting and jealous backbiting are thus the order of the day. What’s more, the products of an artist’s labor are highly susceptible to forgery and fakery: The essence of painting, after all, is to deploy flat daubs of oil to conjure the illusion of physical substance or spiritual gravity. By using superficial means to convey depths of significance, an artist creates a ready medium for hidden messages, trompe l’oeil effects, and other forms of trickery.

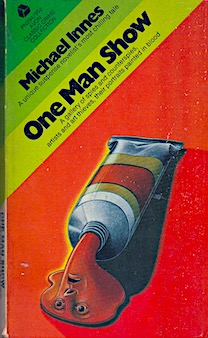

Innes draws on that latent capacity for spite and connivance to build an enticing setup for this title in his long-running series devoted to John Appleby, who has now risen to the rank of Assistant Commissioner of Scotland Yard. Appleby’s wife, Judith, entreats her somewhat philistine husband to join her at a show of works by the recently deceased painter Gavin Limbert.  She too is an artist, a sculptor who hopes to find a canvas with “strong diagonals” that might serve as a suitable backdrop to her work, and Limbert’s abstract style appears to fit the bill. The scenes that take place at the show provide Innes with an ideal opportunity to flex his satiric muscles, and they make up the best part of the novel. Light social comedy gives way to sudden drama when, practically under the noses of the assembled connoisseurs, thieves abscond with the last and most striking work to emerge from Limbert’s brush. Meanwhile, a young woman artist who lived in a flat above Limbert’s studio in Chelsea has gone missing. And, in an ostensibly separate development, two paintings of considerably more illustrious pedigree than the stolen Limbert—a Vermeer and a work by George Stubbs, a fabled painter of horses—have disappeared as well. Soon enough, Appleby is pulling the thread of a criminal scheme (or schemes) of unknown dimension. Then there is the untimely demise of Limbert, a young man of promise: He appears to have shot himself. But did he, really?

She too is an artist, a sculptor who hopes to find a canvas with “strong diagonals” that might serve as a suitable backdrop to her work, and Limbert’s abstract style appears to fit the bill. The scenes that take place at the show provide Innes with an ideal opportunity to flex his satiric muscles, and they make up the best part of the novel. Light social comedy gives way to sudden drama when, practically under the noses of the assembled connoisseurs, thieves abscond with the last and most striking work to emerge from Limbert’s brush. Meanwhile, a young woman artist who lived in a flat above Limbert’s studio in Chelsea has gone missing. And, in an ostensibly separate development, two paintings of considerably more illustrious pedigree than the stolen Limbert—a Vermeer and a work by George Stubbs, a fabled painter of horses—have disappeared as well. Soon enough, Appleby is pulling the thread of a criminal scheme (or schemes) of unknown dimension. Then there is the untimely demise of Limbert, a young man of promise: He appears to have shot himself. But did he, really?

Jacques Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor labeled this novel Innes’s “masterpiece,” perhaps with punning intent but in any case with an excess of praise. After a strong opening, One Man Show devolves into a rickety, random tale in which a great many men (and one woman) scurry about London and its environs in search of missing paintings and missing people. This part of the novel borrows tropes from the police procedural and thriller genres, it reworks those tropes into a manic sequence of escapades that border on parody, and it goes on at tiresome length. First Appleby and then his wife and then his loyal lieutenant, Inspector Cadover, chase a series of leads that put them in contact with as many as four criminal gangs. For the average reader, if not for the average fictional investigator, keeping track of each gang—or indeed of how many gangs there are—is likely to be impossible.

The denouement features a striking twist that helps redeem the belabored antics that precede it. In one stolen painting, as it turns out, there is a great deal more than meets the casual eye. Appleby sees both beneath and beyond the surface of that work, and thereby unravels an entire skein of mysteries. Yet Innes, while he is fairly playful in his treatment of clues, hardly plays fair with his readers: The story that Appleby tells to explain how he solved the case depends on information and leaps of intuition that are available only to him. If this awkwardly plotted tale has a saving grace, it lies in the matchless flair that Innes brings to every stroke of his writer’s pen. With only the inert and monochromatic medium of English prose at his disposal, he renders a vibrant picture of a world filled with evocative signs and everyday wonders.