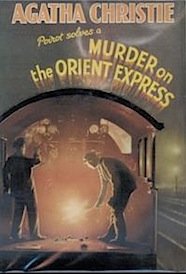

Even those who know in advance how this novel ends, by hearsay or because they have seen the blockbuster movie version that starred Albert Finney as Hercule Poirot, can find a lot to appreciate in its virtuoso display of economical construction and intricate clueing. To be sure, in her delineation of character, Christie applies a very extreme sort of economy: None of the window mannequins who people this tale has an ounce more substance than he or she needs to hold up the most threadbare cloak of homicidal motive. Nor, in setting those characters in motion, does Christie offer more than a polite nod in the direction of social or situational realism. Yet, once entrusted to her narrative care, a reader comes to view those and other conventional literary considerations as extraneous to the business at hand. What matters, instead, are the details—the minute particulars that ordinarily wouldn’t matter at all, but that attain an engrossing, revelatory power once the spotlight of a criminal investigation shines upon them. Why is there a spot of grease on that Hungarian passport? To whom does this handkerchief, the one that’s monogrammed with the letter H, belong? When did the victim’s watch stop, and does that time coincide with the time of his killing?

And the victim himself? He’s a mere vehicle, a purely synthetic contrivance. Taking a cue from the Lindbergh kidnapping case, Christie posits a man who once abducted and murdered a child named Daisy Armstrong. She then places that fiend on a train, the renowned Orient Express, and surrounds him with fellow passengers who each have a connection to the Armstrong affair. When he turns up dead one morning, with numerous stab wounds in his gut—enough of them to give new meaning to the word “overkill”—there are plenty of suspects to interview and plenty of clues to ponder. Foul weather in the Balkans halts the train on its journey from Istanbul to Paris, but Poirot is onboard to keep the murder inquiry on track. Poirot’s presence on the scene counts as another contrivance, in a novel that relies on flagrant plot gimmicks even more than most novels by Christie do. But the transparently contrived nature of Christie’s plotting in this work only serves to put her greatest strength in high relief. Christie might stretch and indeed cross the bounds of probability, but she achieves with enviable ease what every fiction writer at some level yearns to accomplish: She creates a world where the most mundane facts routinely take on a vivid and telling significance.

And the victim himself? He’s a mere vehicle, a purely synthetic contrivance. Taking a cue from the Lindbergh kidnapping case, Christie posits a man who once abducted and murdered a child named Daisy Armstrong. She then places that fiend on a train, the renowned Orient Express, and surrounds him with fellow passengers who each have a connection to the Armstrong affair. When he turns up dead one morning, with numerous stab wounds in his gut—enough of them to give new meaning to the word “overkill”—there are plenty of suspects to interview and plenty of clues to ponder. Foul weather in the Balkans halts the train on its journey from Istanbul to Paris, but Poirot is onboard to keep the murder inquiry on track. Poirot’s presence on the scene counts as another contrivance, in a novel that relies on flagrant plot gimmicks even more than most novels by Christie do. But the transparently contrived nature of Christie’s plotting in this work only serves to put her greatest strength in high relief. Christie might stretch and indeed cross the bounds of probability, but she achieves with enviable ease what every fiction writer at some level yearns to accomplish: She creates a world where the most mundane facts routinely take on a vivid and telling significance.

[ADDENDUM: Today, three quarters of a century after its publication, Murder on the Orient Express enjoys an iconic status in popular culture. It’s a touchstone that anyone can, well, touch in order to summon forth a slew of old-fashioned murder-mystery tropes. Despite the flat quality of its characters, moreover, the urge to bring them to life has been quite strong. In addition to the glossy Hollywood adaptation of the book, directed by Sidney Lumet and released in 1974 to much acclaim, there was an American made-for-TV version, as well as a version made as part of the long-running British TV series Agatha Christie’s Poirot. A mystery-movie spoof, Murder by Death (1976), drew generously from the Christie novel, and an episode of the sketch-comedy series SCTV similarly honored the tale by subjecting it to parodic treatment. And if a final proof of the story’s enduring appeal is necessary, it arguably comes in the form of Agatha Christie: Murder on the Orient Express (2006), a point-and-click computer game. The Orient Express itself is long gone, as are many other features of the genteel world of which it was a part. But the world that Christie contrived in Orient Express goes on—in print, on film, and through the pointing and clicking of PC gamers.]