Take the prison-break plot and the barbed-wire scenery of classic POW-camp movies such as Stalag 17 (1953) and The Great Escape (1963), add a clever murder puzzle, stir in a dash of dry English wit, and the happy result is this hybrid mystery-adventure novel. In fact, those two films appeared after this curiously little-known masterpiece, so the line of influence (if any) likely runs in the other direction. Set during the summer of 1943 in an Italian camp for captured British officers, the story marches forward on three interconnected levels.  Most broadly, there is the world-historic drama of the Allied invasion of Italy, an event whose distant thunder echoes in the background to the brief, tension-wrought scenes that unfold here. One level down, there is the saga of 400 scheming Brits and the boarding-school exploits that make up their campaign to burrow out of the camp before the Carabinieri, the Nazis, and the spies within their own ranks can stop that effort. Finally, there is a tale of death and detection. The slain body of a Greek prisoner, who might have been one of those spies, turns up beneath a pile of sand in an escape tunnel, and the Fascist swine who runs Campo 127 charges another inmate with the crime. Did a member of the British escape team commit murder in order to prevent discovery of the tunnel? It falls to another prisoner, a scholarly sort named “Cuckoo” Goyles, to investigate the matter. The exposition of his sleuthing gets muddled somewhat, as larger forces sweep through the camp—and hence through the book. Still, even amid chaotic wartime conditions, the spirit and the habits of English justice prevail.

Most broadly, there is the world-historic drama of the Allied invasion of Italy, an event whose distant thunder echoes in the background to the brief, tension-wrought scenes that unfold here. One level down, there is the saga of 400 scheming Brits and the boarding-school exploits that make up their campaign to burrow out of the camp before the Carabinieri, the Nazis, and the spies within their own ranks can stop that effort. Finally, there is a tale of death and detection. The slain body of a Greek prisoner, who might have been one of those spies, turns up beneath a pile of sand in an escape tunnel, and the Fascist swine who runs Campo 127 charges another inmate with the crime. Did a member of the British escape team commit murder in order to prevent discovery of the tunnel? It falls to another prisoner, a scholarly sort named “Cuckoo” Goyles, to investigate the matter. The exposition of his sleuthing gets muddled somewhat, as larger forces sweep through the camp—and hence through the book. Still, even amid chaotic wartime conditions, the spirit and the habits of English justice prevail.

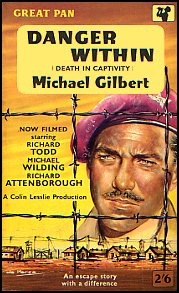

MICHAEL GILBERT. The Danger Within (1952).

19

Apr

TomCat

April 25, 2011 at 5:48 AM

This is one of my favorite post-GAD era mysteries, and one of the more successful blends of the formal detective yarn with the thriller/adventure story – and has a neat and original impossible murder to boot! It’s also semi-autobiographical, which adds an extra layer to an already near perfect book (the recent reprint edition from the Rue Morgue press has a great introduction).

Mike

April 25, 2011 at 12:03 PM

Thanks for your comment, TomCat. I appreciate the additional points that you’ve added to my write-up on this fine little tale. (I’d forgotten that the murder puzzle was of the impossible-crime variety.) By my personal and perhaps overly loose standards, this is a Golden Age detective story. Though published in the 50s, it very much seems to be a book of the 1940s, not just in content but also in style and spirit, and to my mind the 40s were quite definitely a golden era in the history of literary detection. I own just the 1980s Perennial edition of the book, but I’m eager to check out that intro to the Rue Morgue edition that you mention.

TomCat

April 25, 2011 at 1:00 PM

Well, it’s difficult to exactly pinpoint the rise and decline of the golden era, but I loosely place it between the early 1920s (arrival of the Crime Queens) and the early 1950s (when publishers started to favor suspense, thrillers and hardboiled stories over puzzle-plot orientated mysteries). The 1940s were definitely part of the great era of detective stories and was one of the genre’s biggest boom periods (established writers published some of the best works, new writers like Kelley Roos, Edmund Crispin and Christianna Brand made their debuts and countless of reprints of classics from previous decades).

That’s why I indicate every published after 1949 as post-GAD.

Mike

April 26, 2011 at 2:25 PM

TomCat:

I agree, on all points. Someday I’d like to write a piece on how the 1940s were truly the most golden of eras for the publication of detective stories written in the classic manner. Leading writers had not yet abandoned or tired of the apparatus of puzzle plotting (clues, maps and timetables, trick endings); indeed, they had developed it into a high art. Meanwhile, though, they had found ways to incorporate into their work certain literary elements (brisk pacing, subtle characterization, social commentary, satire) that were generally absent or imperfectly deployed in earlier detective novels. Most of my favorite works by Carr (Case of the Constant Suicides), Christie (Murder in Retrospect), and Queen (Calamity Town) come from the early and mid 40s, for example. Several other novels in my canon of all-time favorites also appeared during those years: Green for Danger, by Brand; Cue for Murder, by McCloy; The Big Clock, by Fearing. I also like Chandler’s work from that period. Unlike so many private-eye tales that came in his wake, his first several novels (such as The High Window) contain real mysteries and feature real detection.

So you tapped a nerve. You’ve also (here, and on your excellent blog, Detection by Moonlight) planted a seed for me to check out Kelley Roos. Thanks.